I do want to expand my universe. I do want to expand my sensitivity, my understanding, my concern. We all want to change the world – not by being aggressive, but by being committed. And by being flexible enough to change.

-Saviz Shafaie, The Orlando Sentinel, 1992

Saviz Shafaie (1950-2000) was a steadfast advocate for LGBTQ rights. In 1982, he moved to Central Florida, where he pursued a graduate degree in social work from the University of Central Florida, opened the popular Power House restaurant in Winter Park, and founded the activist organization We the People. Shafaie was an immigrant, activist, and business owner – to understand his story is to recognize the way these identities intersect.

The Immigrant

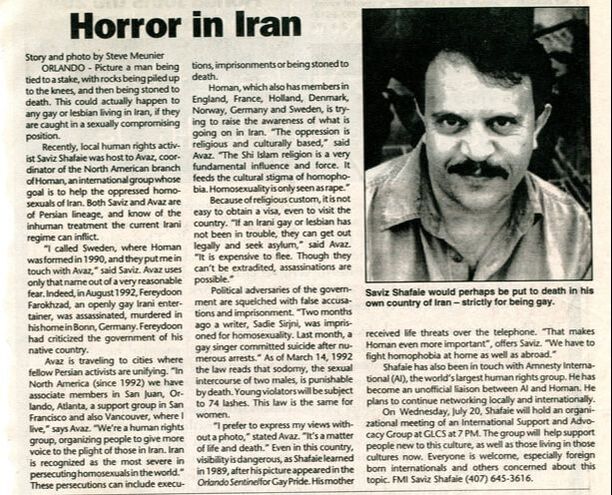

In this article published in “The Weekly News,” Shafaie and Avaz, the coordinator for the North American branch of Homan, describe the gruesome punishments faced by gay Iranians. While Avaz remains unphotographed fearing retribution, Shafaie’s image is a bold defiance with potentially deadly consequence.

In this article published in “The Weekly News,” Shafaie and Avaz, the coordinator for the North American branch of Homan, describe the gruesome punishments faced by gay Iranians. While Avaz remains unphotographed fearing retribution, Shafaie’s image is a bold defiance with potentially deadly consequence.

Shafaie was born in Iran on August 30, 1950. During his lifetime, his native country underwent sweeping changes beginning with the 1953 coup d’état that overthrew nationalist Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh and strengthened the monarchial rule of the pro-Western Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. Pahlavi’s modernization policies were a source of controversy that led to mounting political tension with leftists and Islamists, eventually leading to the 1978-79 Iranian Revolution that replaced the monarchy with an Islamic Republic. Shafaie was among the growing number of Iranian immigrants who came to the United States to attend university and stayed as refugees following the Revolution.

Prior to immigrating, Shafaie studied sociology at the University of Shiraz, where he became increasingly fascinated by questions surrounding sexuality. Within Iran, homosexuality was more visible and accepted prior to the Revolution, after which it was outlawed and punishable by death. Shafaie’s interest in homosexuality culminated in 1972 with his delivery of a presentation on the subject that attracted hundreds of students. Moving to the US in 1976, he pursued his master’s degree from Syracuse University. Sociology offered a lens for Shafaie to better understand himself and his sexuality, resulting in his coming out as a gay man. “I was reading passionately and growing more solid, free, and open,” Shafaie said. “Public speaking, first under the safety of an academic roof resulted in dialogue and finally encouraged me to be more outspoken and honest. I eventually felt I knew enough to overcome my fear and insecurity. I had a sense that I owed it to myself to be open.”

At times, Shafaie’s homosexuality and his Iranian heritage were at odds. He experienced first-hand the oppression faced by gay Iranians both in their home country and the United States. After the Orlando Sentinel published an article about his involvement in the gay rights movement, members of an Iranian American peace gathering—a group Shafaie founded—asked him to leave. His mother received threatening phones berating her for having a gay son. One Iranian American woman even asked an Ayatollah, an Islamic religious leader, to issue a decree to expel Shafaie from the Iranian community. Despite this adversity, Shafaie answered discrimination with a call for better understanding and peace. He was also an active member of Homan, an international coalition that fought for the rights of gay Iranians.

Prior to immigrating, Shafaie studied sociology at the University of Shiraz, where he became increasingly fascinated by questions surrounding sexuality. Within Iran, homosexuality was more visible and accepted prior to the Revolution, after which it was outlawed and punishable by death. Shafaie’s interest in homosexuality culminated in 1972 with his delivery of a presentation on the subject that attracted hundreds of students. Moving to the US in 1976, he pursued his master’s degree from Syracuse University. Sociology offered a lens for Shafaie to better understand himself and his sexuality, resulting in his coming out as a gay man. “I was reading passionately and growing more solid, free, and open,” Shafaie said. “Public speaking, first under the safety of an academic roof resulted in dialogue and finally encouraged me to be more outspoken and honest. I eventually felt I knew enough to overcome my fear and insecurity. I had a sense that I owed it to myself to be open.”

At times, Shafaie’s homosexuality and his Iranian heritage were at odds. He experienced first-hand the oppression faced by gay Iranians both in their home country and the United States. After the Orlando Sentinel published an article about his involvement in the gay rights movement, members of an Iranian American peace gathering—a group Shafaie founded—asked him to leave. His mother received threatening phones berating her for having a gay son. One Iranian American woman even asked an Ayatollah, an Islamic religious leader, to issue a decree to expel Shafaie from the Iranian community. Despite this adversity, Shafaie answered discrimination with a call for better understanding and peace. He was also an active member of Homan, an international coalition that fought for the rights of gay Iranians.

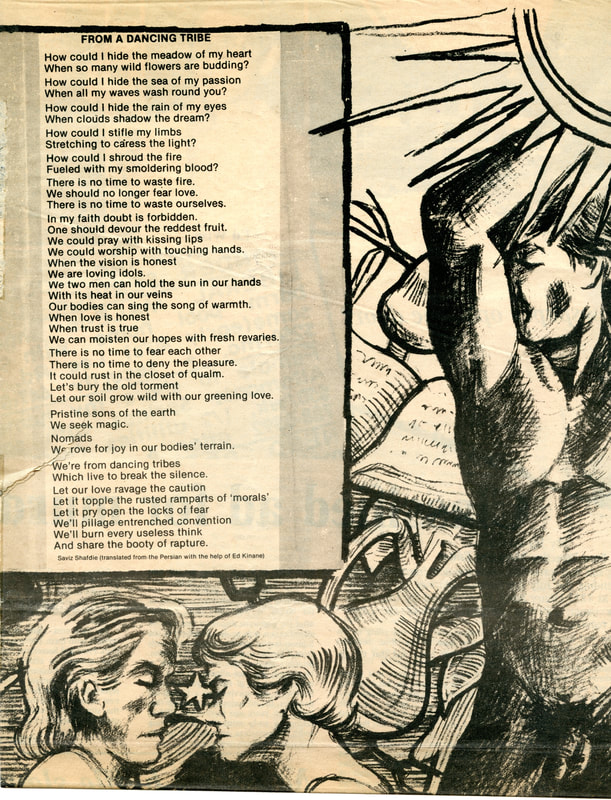

Although he was outspoken in his position against the Islamic Republic’s fundamentalism, Shafaie continued to embrace his Iranian heritage after moving to the United States. In Central Florida, he organized celebratory gatherings for Nowruz, the Persian New Year. He also wrote poetry in Persian and studied Persian poets like Rumi and Hafez. Consider Shafaie’s poem, translated from Persian, “From a Dancing Tribe.” While you may read this as a poem about love between two men, how might Shafaie’s experience as an immigrant—balancing clashing values and traditions—also inform the narrative?

The Activist

Shafaie was a proponent for many progressive ideas, fighting for minority rights through peaceful activism. In addition to his work with Homan, Shafaie was a founding member of We the People, a Central Florida coalition of gay and lesbian individuals broadly advocating for human rights. Founded in 1988 and active throughout the 90s, We the People planned peaceful protests within the region and organized local members for state and national demonstrations. Though they often supported gay rights issues, the organization’s values were not identity-specific, stating in their founding documents:

We chose our name carefully to reflect our concern both for ourselves as survivors of oppression and for others who also survive it daily. There is no longer any question of working against one type of oppression and turning away from another.

-WE THE PEOPLE, 1988

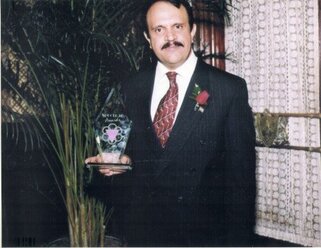

For his work as an activist and leader, Shafaie was awarded twice at the Spectrum Awards, the Gay and Lesbian Community Services of Central Florida’s annual award ceremony that recognized the important work of community members. In 1995, Shafaie received a Spectrum Award for his efforts at promoting recognition of diversity within the region. In 1997, he and partner Jim Ford – a fellow cofounder of We the People – received a joint Award recognizing them as male activists and community role models.

The Business Owner

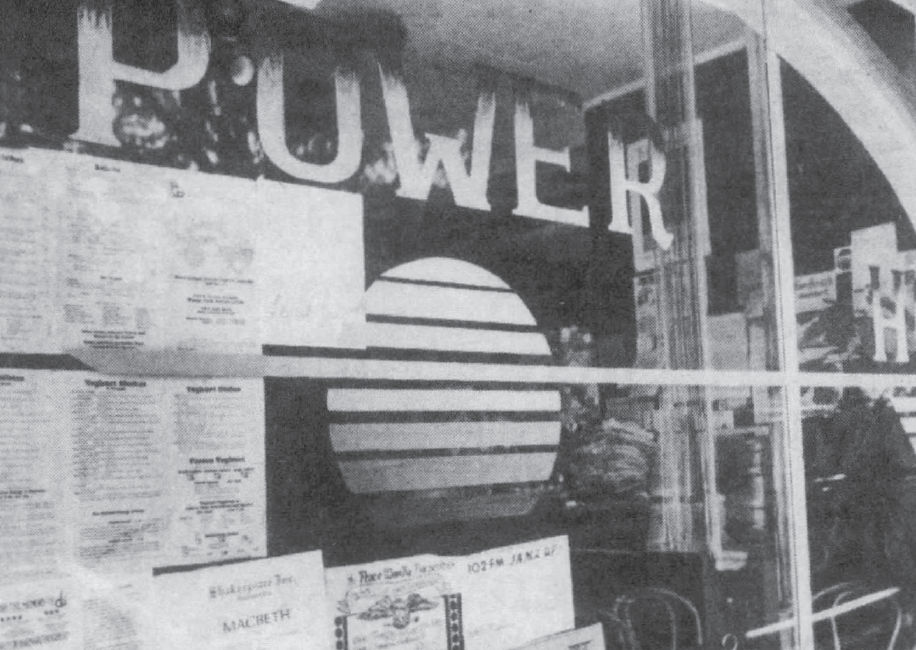

After Shafaie moved to Central Florida in 1982, he opened Power House as a space for “healthy food and healthy discourse.” In this small restaurant located off Winter Park’s busy Park Avenue, “alternative lifestyles” were accepted, discussed, and celebrated. Shafaie lined the walls with posters that advertised protests, boycotts, and membership information for activist organizations. The counters were filled with rack cards, buttons, and t-shirts that all boasted progressive, activist slogans. One highlight was the restroom, which Shafaie kept stocked with pens to encourage patrons to write their opinions on the papered walls. The writings were an artwork, and Shafaie preserved them by covering them in plastic.

Shafaie owned and operated Power House with his mother, Maheen Shaghaghi. In pre-Revolution Iran, Shaghaghi protested the violence incurred by Iranians under Pahlavi. She believed in fighting for the rights of others, telling the Orlando Sentinel, “I cannot tolerate any injustice.” After she immigrated to the US, Shaghaghi lived with Shafaie and met other members of the gay community. This experience inspired her to work alongside her son to defend the rights of others. She and Shafaie operated Power House with this intention until they sold the business in 1998.

Shafaie passed away in 2000 from cancer. His friend Jack Nichols wrote that Shafaie was unafraid to die because he lived a life of which he was rightfully proud. After his death, Shaghaghi donated her son’s scrapbooks to the Museum – the collection that this exhibition draws from. The scrapbooks document Shafaie’s intersecting interests and efforts as an immigrant, activist, and business owner, a legacy that continues to inspire.

Shafaie owned and operated Power House with his mother, Maheen Shaghaghi. In pre-Revolution Iran, Shaghaghi protested the violence incurred by Iranians under Pahlavi. She believed in fighting for the rights of others, telling the Orlando Sentinel, “I cannot tolerate any injustice.” After she immigrated to the US, Shaghaghi lived with Shafaie and met other members of the gay community. This experience inspired her to work alongside her son to defend the rights of others. She and Shafaie operated Power House with this intention until they sold the business in 1998.

Shafaie passed away in 2000 from cancer. His friend Jack Nichols wrote that Shafaie was unafraid to die because he lived a life of which he was rightfully proud. After his death, Shaghaghi donated her son’s scrapbooks to the Museum – the collection that this exhibition draws from. The scrapbooks document Shafaie’s intersecting interests and efforts as an immigrant, activist, and business owner, a legacy that continues to inspire.

This exhibition was organized by Rollins College student Devorah Burgess as part of the course History of American Sexuality.

Learn More About the Partnership

Learn More About the Partnership